Do you have the courage to be disliked? (Or: Rethinking how to deal with criticism)

A muscle every creative person should exercise.

“No experience is in itself a cause of our success or failure. We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences—the so-called trauma—but instead we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.”

- The Courage to be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga

I’ve been thinking a lot about the role of criticism for a creative practice this week. And I couldn’t possibly write about this topic without mentioning an obvious source: The Courage to Be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga. I’m often sceptical of books people describe as ‘life-changing’, but I listened to this as an audiobook recently and found there was a lot of value to be gained here. The book is essentially a distillation of concepts based on Alfred Adler's philosophical ideas. It got me thinking…

The courage to be disliked is the courage to stay the course, do what you most want to do, and reassess how you take on the opinions of others. I came away with a few important ideas about criticism as a useful force; painful as it might be, criticism is both essential to the process of artmaking and far more positive than it first appears.

How can external criticism benefit your creative practice?

Developing and discerning your taste.

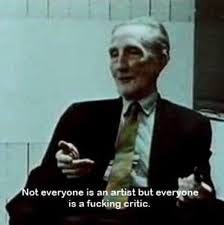

I love this image of Marcel Duchamp. I look at it regularly in order to remind myself that the very act of making anything is courageous, just as a starting point. everyone thinks their opinion about books or TV or movies is valid - and in many ways, the aesthetic judgement is subjective. Critics insist they have greater insight into these judgements, because they perhaps admire the technical elements without necessarily being artmakers themselves. This isn’t to denigrate the critic; having discernment (or taste) is essential to both the critic and the artist. After all, without a sense of what you like and appreciate, how do you ever figure out what it is you want to make?

The fact that everyone thinks their own criticism of aesthetic objects/works are valid often means that everyone thinks their taste is superior. How do we square this with the fact that artists themselves have to have “more” of a sense of what works aesthetically, because they operate precisely to make their taste known? It’s a woolly subject area, but the great benefit of engaging with critics (be they professionals, your parents, your best friend, your partner, or an anonymous Amazon review) is that you can start to get a feel for your own aesthetic preferences. Unless subjected to push back, your taste might never be challenged. You might never have to exert your taste anywhere; it might never be subject to scrutiny and therefore you might never refine that taste - hone it in any direction. A quote I found recently that I liked was this:

“The trouble with most of us is that we’d rather be ruined by praise than saved by criticism.” — Norman Vincent Peale

We want praise because it feels good. Praise given without any dissent is a seductive idea that will ruin our capacity to make better art. Why? Because being spoiled by always being agreed with is the way of the dictator and egomaniac - without criticism, we assume our taste is superior, we never question our choices, and we subsequently aren’t pressured to figure out what it is we actually even really like. We just like what we like without question. We react against things, as well, without cause. Being pushed to determine our preferences, to really think and feel them, helps us figure out what we want to make next. In other words: Criticism can be generative.

Getting perspective on your tasks as an artist.

“Let me never fall into the vulgar mistake of dreaming that I am persecuted whenever I am contradicted.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

Criticism isn’t a persecution. It’s easy to see it that way sometimes. It’s also so tempting to retreat to safety instead of putting your work out there and subjecting it to comment. But given that artmaking requires courage and vulnerability, the practice of acquiring feedback can act as an important exercise, building the muscles of courage in order to do more singular and risky work. I think that risk is my job - it is my job to challenge, rethink and dream up scenarios that demonstrate curiosity in the world and its people. That is my task.

In the Courage to Be Disliked, one of the key ideas is that every problem we have is an interpersonal relationship problem (because we are interconnected and social beings). As a result, many of us want to be loved by other people. But by seeking out praise over contradiction (in order to feel accepted), we start to become overly concerned with what others think of us.

Adlerian psychology suggests that being overly concerned with other peoples opinions of us - other people’s tasks - is a problem. Their opinions, their tasks, are not our business. Our business is what we can control. While this might seem a bit scary - like all the blame for bad work lies with us - it can also be empowering. After all, the power to make great work is also ours to impact. We are not responsible for other people’s tasks.

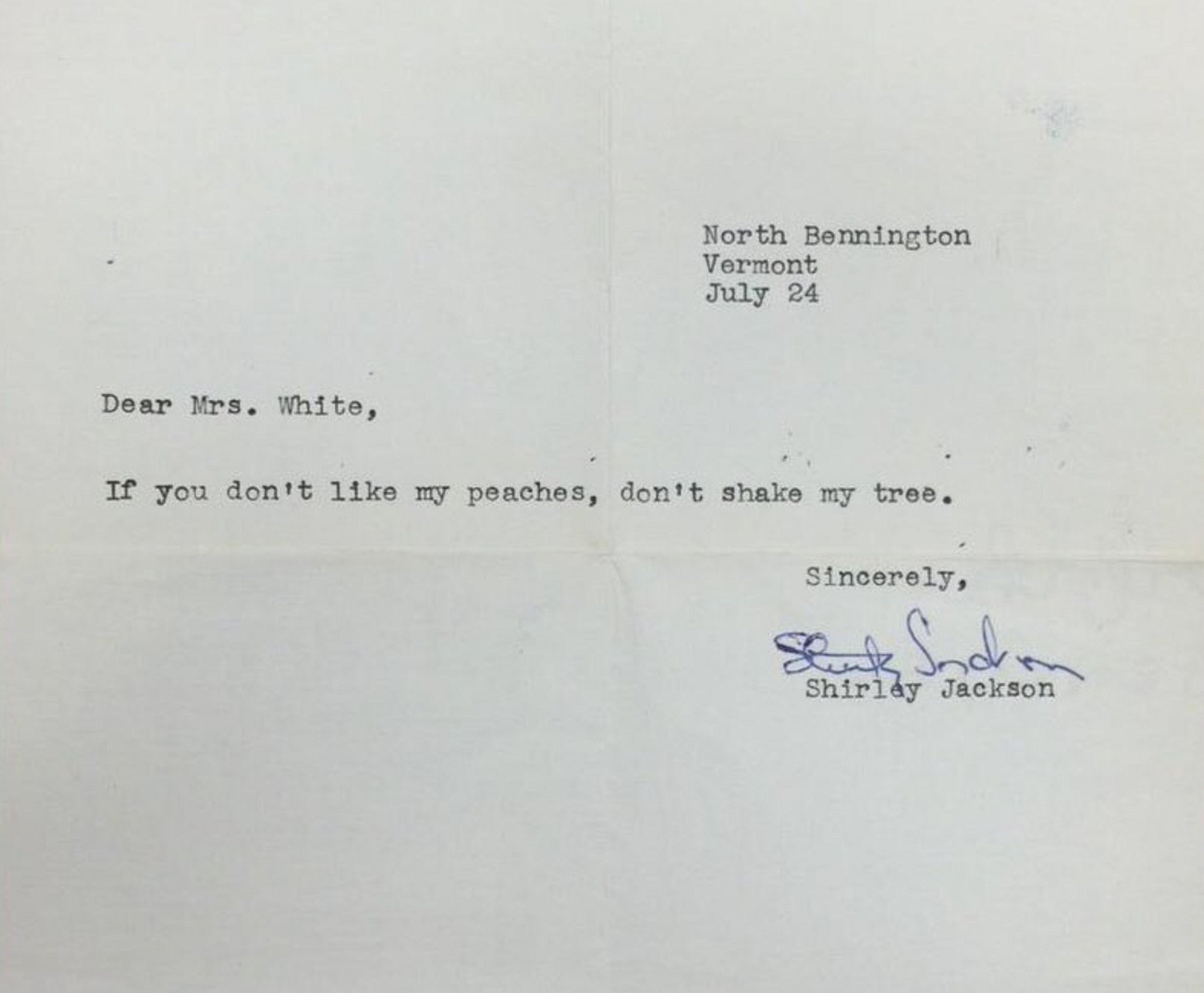

The indifference John Berryman describes above is a great reminder for the kind of perspective we can take on our own role - it is not our role to sit back and be praised or blamed. We can’t use either vanity or self-pity to improve our work. And ultimately, my role is to make better art. Whatever that means to me, it is my role to find out how to get there. In other words, being an artist is a very specific kind of role, and it’s important to put that role in perspective: Only I can give myself the permission to create art, and do it to my own satisfaction. Those are my tasks. The opinions others have of my work can be helpful and informative, but controlling how others feel about my work is not my task. It’s thus not my task to either force people to engage with my work in a particular way, nor is it my task to have them approve of it. I feel like this letter Shirley Jackson wrote to a disgruntled reader sums it up fairly well:

Criticism can offer you a place in the community.

“Writing is very difficult, but so is any job carefully executed. What is a privilege, however, is to do a job to your own satisfaction.”

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Something that I’ve realised recently is that if someone is engaging with your work - in any way, shape or form - that’s a really wonderful thing. For so long as a writer, you sit alone in a room with no feedback of any kind. To have someone actually read your words is a great privilege. One of the core elements of Adlerian psychology states that while the separation of tasks can help us realise we are not responsible for the opinions of other people, we still crave community - if you are the only person who can achieve real happiness, then being fully and solely responsible for this fact could feel pretty lonely.

While the separation of tasks is a great tool to figure out what you can actually control and impact, it’s actually also a way into more positive and equal interpersonal relations. A sense of belonging is something you acquire through your efforts (be it as an artist or just as a person more broadly); it’s not something just endowed at birth. By thinking beyond yourself and focusing on your contribution to something larger, like the community around you, the world, and the universe, you can acquire a sense of belonging.

By being acknowledged as an artist who is trying to make a contribution to the wider art world (no matter the discipline), you are on your way to earning a place - to being acknowledged as a true contributor in that world. No contribution - whether people like it or not - comes all that easy. But the joy is in a job well done, particularly to your own satisfaction. As Gabriel Garcia Marquez said in the quote above, a job well done to your own satisfaction is a real privilege. And so is anyone choosing to engage with it. In short: when you are offered feedback, be it critical or not, you are being offered confirmation that you are indeed working towards your place in this world of creativity and artmaking. Your task (i.e. to make art) has been satisfied - you’ve satisfied your role. Anything beyond this is gravy.

Final thoughts, for now..

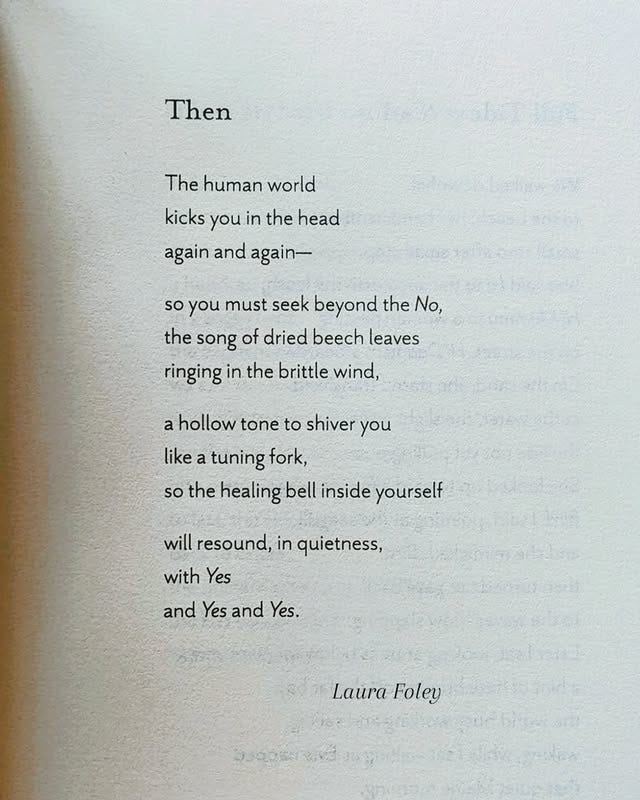

Seeking out the healing bell inside yourself, as this beautiful poem by Laura Foley suggests, is a great way to also think about the task of being an artist. There are a million ways we might put this otherwise, but this one resonates with me. I am seeking out the healing bell, the sound of Yes, and while I will hear criticisms given to me, I must hold these lightly and with good perspective in light of my own tasks.

Criticism can help me figure out what I really think is important to lean into or away from in my own work. But it also reminds me of the great privilege of doing this difficult work, challenging me to remember the most important tenets of my role as an artist. It gives me perspective, and a place at the table beside artists of all stripes.

Do you have the courage to be disliked, and rethink criticism?

Until next time,

Be well.

CCx

A little something extra…

Submissions are now open for glut’s next edition! Take a look at our full submissions guidelines here or catch up on our first edition to get a sense of our taste.

Do you know a writer who should submit? Please pass this on! We’re eager to read your words and will also open for photography submissions soon. Any questions, send us an email.